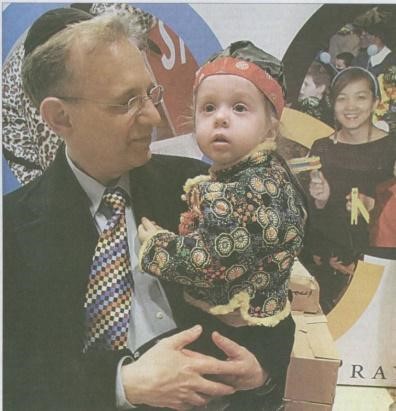

Akiva Pearlman

Akiva Pearlman

Born: Seattle, Washington

Raised: Chelmsford, Massachusetts

University of Massachusetts, BA Chinese

Kung Fu Master

There is an apocryphal story about a young Jewish man who in his spiritual quest had travelled the world, worshiping in Native American sweat lodges, taking ayahuasca in the jungles of the Amazon under the guidance of a native shaman, experiencing a Catholic Mass at the Vatican, bowing on a prayer mat in Mecca and eventually reaching a mountain peak in the Himalayas where he met a famous Buddhist guru. In answer to the traveller’s question as to the meaning of life and what his path through it should be, the guru, who was alternatively an old Jew from Brooklyn or the Dali Lama, answered with a question: “Who are you, my son?” “A Jew from New York,” answered the traveller. “What are you doing here? You should look into your own traditions. Go to yeshiva in Israel.” He did, ending up in Ohr Somayach and eventually becoming a great talmid chacham. This is not Akiva’s story. It’s nothing compared to his.

Akiva grew up in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, after his family moved there from Seattle when he was two years old. They were a very secular family and he grew up without knowledge of Shabbat, Rosh Hashanah or even Yom Kippur. They did try Chanukah for a couple of years, but reverted to Xmas the next. One might say, they couldn’t see the forest for the Tree. But, they knew they were Jews and were proud of it, although Akiva and his siblings had no idea what it meant to be Jewish.

He was a very curious and precocious child. He was artistic and loved reading. He also loved science and mathematics. When he was ten years old, his aunt gave him a camera as a birthday present. It was wrapped in a newspaper from Japan. He was as excited about the newspaper as he was about the camera. He was fascinated by the mysterious and seemingly unintelligible characters. He announced to his mother that one day he was going to be able to read that newspaper.

By the end of high school he wasn’t sure what he wanted to study. His mother suggested that since he could draw so well, he should study art. Akiva received a full scholarship to study art at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. One of his first art classes was taught by Professor Wong, a Chinese professor and a well-known Chinese artist. Akiva loved the professor, who peppered his lectures with Chinese philosophy. After criticizing one of Akiva’s paintings, he said to him: “Not everyone can be a good artist, you know.” Taking the criticism to heart, Akiva dropped his major and switched to the study of Chinese.

He was a fast learner, but after two-and-a-half semesters of Chinese he felt the tug of the sciences, and decided to drop out of the University to study Chinese medicine. With almost no money in his pocket, he hitchhiked to the West Coast, where he hoped to save up enough money for a one-way ticket to Taiwan. In those days Mainland China was closed to foreigners. He eventually got to Taiwan and began studying the Chinese language in earnest with the purpose of entering a Chinese medical school or getting an apprenticeship with a Chinese doctor.

Ever the perfectionist, Akiva insisted on mastering Mandarin so that he could speak without an accent. His teacher told him

that this was impossible. There were no foreigners who could master the tonal subtleties of the Chinese language. He would always sound like a foreigner. However, instead of discouraging him, it only made him try harder. He spent weeks on mastering the difference between only two words that initially sounded exactly the same to him. He then returned to the teacher, who told him that she couldn’t believe what he had accomplished. After a few years his Chinese was impeccable. (I can attest to this fact, because I have been to kosher Chinese restaurants in New York with Akiva, and the owners have told me that they are astounded at how he speaks Chinese perfectly and without an accent.)

In addition to studying Chinese, Akiva also studied art, music and Kung Fu — Chinese martial arts. One day he heard about a renowned Chinese doctor who was located at the base of a mountain in Central Taiwan. He travelled there and began learning traditional medicine from him. At the top of the mountain was a Buddhist monastery headed by an even more renowned master Chinese healer and Kung Fu expert, a true shifu (master teacher). Akiva asked the master if he could learn from him. The master told him that he could, but he would have to follow all the rules of the monastery. Akiva agreed, with the proviso that he wouldn’t have to become a Buddhist monk. The monk’s day began at 3 am. Upon waking, the monk was required to drink 14 large bowls of water. This was followed by an hour of strenuous exercise and difficult pushups. When he arrived, Akiva could do 19 pushups. All of the other monks were doing hundreds. The master told him to add one pushup a day. (By the end of his stay he was doing 685 pushups without a break.) After bathing in a nearby mountain spring, the monks would have a large breakfast and then tend to the daily chores, such as vegetable gardening and carrying huge buckets of water on their backs from the mountain spring to irrigate the monastery’s gardens below.

Lunch was a bowl of rice and a bowl of water. A mid-day break was devoted to Buddhist study, including Kung FuMeditationand calligraphy. They also made excursions into town to help the needy and the sick. They went to sleep at nightfall. After many months of this regimen, Akiva began to question whether the master would ever teach him Chinese medicine and martial arts. He knew he was being tested but he couldn’t wait forever.

After three long years at the monastery, Akiva finally left. He had waited long enough. He was 23 years old and restless. He consulted with a few wise men as to his future and they all told him he should return to the States and get his undergraduate degree. He did. He completed his missing three years of college in one year, with a 4.0 average, and graduated with a degree in Chinese. Upon graduation he returned to China and began working as an English teacher to support his medical studies. After a “chance” meeting with a famous Chinese Kung Fu movie director, he was hired to play a bit part in a new movie. The director also hired him to tutor the star of the film in English. In the course of the lessons, the actor discovered that Akiva knew martial arts. Many of the Kung Fu movies at the time had a white American Kung Fu master as its antagonist. With his command of Chinese and martial arts, Akiva was a cinch to play the bad guy in the movies.

After a successful, but relatively brief acting career, Akiva moved to Japan, where he again pursued his desire to learn Chinese medicine. He mastered Japanese in a year but failed to find the right school in which to learn medicine.

Around this time Akiva’s father passed away and he began to contemplate the meaning of life in earnest. Until then, although a Buddhist monk, he was an atheist. But he also had a deep sense that there was something much deeper going on in the world than the phenomena that met the eye. He threw himself into the teachings that he had previously learned only superficially as a monk, examining Christian scriptures as well. Nothing satisfied him. There were too many unanswered questions and contradictions. He made a trip back to Boston to visit his mother and sent himself three large boxes of Jewish books from the local Jewish bookstore in Brookline. Back in China he had pored through these books. One of them mentioned the idea from the Sefer HaChinuch that if someone observes the mitzvahs constantly, eventually he will come to believe in

After a few zmanim in the Yeshiva, he made the decision to move to New York and find his zivug. He met his aishes chail after a long and grueling eight-year search. At the behest of a large US kashrut organization, the couple moved to Shanghai, where Akiva set up their China office. After a number of years, the family moved to Beijing, where Akiva was hired by a large Israeli Real Estate development company to establish its Chinese branch and to be its COO. In 2018, after 14 years and three children, the family moved from Beijing to Cleveland, Ohio, where Akiva is today employed as the COO of a large Mid-West real estate concern, and a staunch member of the Orthodox Jewish Community.