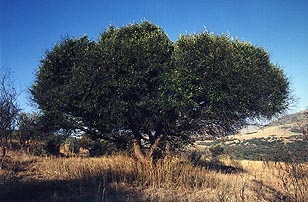

A Tree Grows in Israel

| "I think that I shall never see A poem lovely as a tree. Poems are made by fools like me, But only G-d can make a tree." Joyce Kilmer, "Trees" |

The poet sees the hand of Hashem in a tree. But why specifically a tree? Why not a stone, or a river, or a zebra for that matter?

"When you besiege a city for many days to wage war against it to seize it, don't destroy its trees ... for from it you will eat ... is the tree of the field a man that it should enter the siege before you?" (Deuteronomy 20:19)

The verse states openly that it is forbidden to cut down a fruit tree, and so rule Maimonides as well as all other halachic authorities. What is curious in the verse is the comparison of a tree to man; what does man have to do with the prohibition against cutting down a fruit tree?

Man is like a tree in that his good deeds are his

produce, his "fruits," and his arms and legs the branches

which bear these fruits. He is, however, an "upside-down

tree," for his head is rooted in the heavens, nestled in

the spiritual soils of the Eternal, and nourished by his connection

to his Creator (Midrash Shmuel on Pirkei Avos 3:24).

Man is like a tree in that his good deeds are his

produce, his "fruits," and his arms and legs the branches

which bear these fruits. He is, however, an "upside-down

tree," for his head is rooted in the heavens, nestled in

the spiritual soils of the Eternal, and nourished by his connection

to his Creator (Midrash Shmuel on Pirkei Avos 3:24).

The first mishna in "Rosh Hashana" teaches that Tu B'Shvat, the 15th day of the month of Shvat, is the Rosh Hashana, or New Year, for trees (according to the school of Hillel). Why do trees need a New Year? Our Sages teach us that although it still looks like the dead of winter, it is not. Deep inside the tree the sap is beginning to rise (the Hebrew word for sap is "saraph" or "fire," striving to rise ever higher and reach its Creator).

Spring approaches, rebirth has begun. And they teach us that just as it is with a tree so too it is for man; since "man is a tree of the field," the "renaissance," the process of rejuvenation in man has begun. The poet appears to subconsciously draw on the metaphor of tree rather than stone, river, or zebra, as the "hand of G-d" can most clearly be seen in the tree, the metaphor for the handiwork of G-d, the human being.