Multiples of Chai

It's 2 O'clock In The Morning...

There's a strangeness about writing in these times. On the one hand, there is the desire to share one's thoughts and feelings with a friend; on the other hand, the pace and nature of events move so quickly as to render yesterday's insights musty, all but antiquated. And, of course, we still don't have the cool distance of perspective that lends the surgical ability to dissect feelings and responses. Still there's a kind of validity in trying to freeze a feeling or two. To catch it on the cooled slide and submit it to the scrutiny of analysis. None of this can yet be conclusion; it is all process.

The First Thing We Knew...

I close my eyes and I see my daughters running

and screaming towards me as the siren screeches overhead to run

for the shelters. The distance as I run toward them seems immeasurable.

Praying together in a shelter adds a dimension to what we call

kavana (concentrated feeling).

I close my eyes and I see my daughters running

and screaming towards me as the siren screeches overhead to run

for the shelters. The distance as I run toward them seems immeasurable.

Praying together in a shelter adds a dimension to what we call

kavana (concentrated feeling).

At 5:30 A.M., down at Shaarei Tzedek Hospital, now a military hospital, I have been waiting in line with the other volunteer drivers to pick up doctors and nurses. Public transportation is practically non-existent. The fellow next to me is a professor of psychology at the university. He studied at the same yeshiva as I in the States. He has a lulav and etrog and a soldier comes over to say a prayer with them. The talk is not one of concern about losing, but one of what price must be paid to win. In one corner of my mind, I see a certain beauty in the breakthrough in the human dimension. Jews non-religious, religious, Western, and Oriental - are in it together and there is a camaraderie, a melting of the icy walls that at other times separate.

The radio says nine of the 11 bridges the Egyptians threw across the Suez have been knocked out. Then later we hear that these temporary pontoon bridges can be rebuilt in four hours.

Dayan sounds a lot more cautious in his appraisals than I would like him to sound. The radio also says that there is no need to hoard, yet the next morning people mob the corner grocery, buying up sugar, flour, noodles, as if planning for a siege. They rush to the bread bins as if it were gold. Later, other people go around asking if some families need bread; they will share what they have.

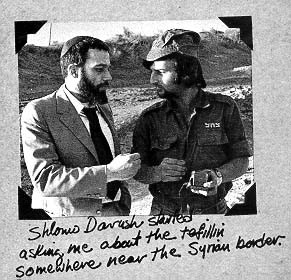

The blackouts have sapped the life from the city at night. People stay close to home. Each night the HAGA (civil defense) come by blowing whistles and hollering for violators to douse their lights.

Even as you function one ear of your mind listens for the siren and you think about what would be the right thing to do - whether or not to listen to the school authorities when they say don't come for your child if there is a siren; they will lead the children to shelters, and parents should go to the ones nearest them.

A theme of being insignificant, as an individual,

as a nation, as the giant meshing gears grind around us. Yet a

certain sense of significance returns with being at the eye of

the storm, with this devastating fulfillment for those lines in

the Prophets. But this significance comes now mitigated with a

fresh humility.

Back Home... | Encounter On The Golan | Now, The Waiting Starts Again...

Hakafot With Soldiers

At the conclusion of Shemini Atzeret, which

is the beginning of Simchat Torah outside of Israel, we drive

in a few cars out to the Jordan Valley. It is a motley group that

drives with us. We have gotten special permission to bring a band

and some rabbis out to an army encampment to make Hakafot Shniot

- a second round of dancing with the Torah Scrolls for the

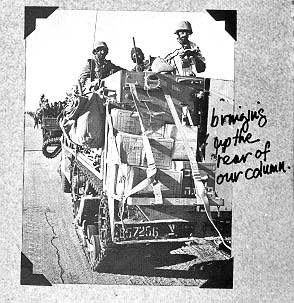

soldiers. Turning off the Jerusalem-Jericho road, we see soldiers

from time to time, their khakis making them look like part of

the desert-dry shrubbery that abounds here. Then we meet our military

escort and we turn on to a dirt road built by the Romans that

connects through to Jerusalem around Wadi Kelt. Conceivably, this

could be used as a tank route, and of course, for armored divisions

by the Jordanians. Our army hosts are there to watch out for that

contingency. As we are told, they would blow up the road were

the Jordanians to being moving.

At the conclusion of Shemini Atzeret, which

is the beginning of Simchat Torah outside of Israel, we drive

in a few cars out to the Jordan Valley. It is a motley group that

drives with us. We have gotten special permission to bring a band

and some rabbis out to an army encampment to make Hakafot Shniot

- a second round of dancing with the Torah Scrolls for the

soldiers. Turning off the Jerusalem-Jericho road, we see soldiers

from time to time, their khakis making them look like part of

the desert-dry shrubbery that abounds here. Then we meet our military

escort and we turn on to a dirt road built by the Romans that

connects through to Jerusalem around Wadi Kelt. Conceivably, this

could be used as a tank route, and of course, for armored divisions

by the Jordanians. Our army hosts are there to watch out for that

contingency. As we are told, they would blow up the road were

the Jordanians to being moving.

But now we see some tents spread out over the sandy desolation. Stark emptiness, except for the presence of the soldiers. We are standing now at the center, which is nothing more than a few communications bunkers dug into the ground and the surrounding tents. We are told that the hills all around are dotted with our men. The first soldiers to greet us, as we pull up in a cloud of dust, are some former neighbors of mine: one, a Yemenite Jew; the other, a Hassidic fellow. It seems as if this is the first time I've seen the Yemenite fellow in uniform; and my first reaction to the Hassid was that it's the first time I've seen him out of uniform. I've never seen such a star-strewn sky - the brightness, the effervescence of the stars is overwhelming. And the sukka. That simple makeshift sukka in the middle of the desert. On the one hand, it seems to belong here more than a sukka belongs anywhere else. On the other hand, there is a certain strangeness in this festive booth in the middle of the stark, empty desert.

One of the soldiers invites a rabbi to speak. This rabbi, an army chaplain, says the Arab attack is an attack upon our people. Our people have been sustained by our tradition throughout our history, a tradition which expresses our trust and belief in God, that He will see us through to victory. And so, when we dance now, with the Torah Scrolls, our dancing is an affirmation of this trust. A tractor, the few cars that we drove in with, and some army vehicles are formed into a circle and the headlights are turned on. A loud-speaker has been attached to one of the batteries of the cars. The Torah Scrolls are carried to the center of the circle. Two long-haired, young soldiers - one with a submachine gun, the other with a rifle slung over his shoulder - hold the Torah by the wood handles at the bottom, pushing it high into the air. The music explodes and soldiers come running to dance. The words of the song are a line from the Prophets expressing belief and trust in God and His Torah. The circle churns, the 15 of us in civilian clothes melding into the khaki swirl of movement. The voices reach and cry with a special kind of defiance. A defiance at those would-be conquerors. The soldier next to me screams, "Sing loud friend, let that mamzer Hussein try and figure this out."

"Nobody has ever made hakafot in

this place," says one soldier. The sand fills up into our

lungs as we dance, and we dance.

There is a break, and one of the soldiers runs

up to the mike and says, "There is another reason for our

simcha tonight." and explains that one of the soldiers' wives

had had a boy only that morning. Somebody brought the message

from Jerusalem with our caravan. The father is dragged out into

the center. A handsome, rugged-looking young man. Two friends

lift him on to a third fellow's shoulders and the singing and

dancing erupt again. At the next pause, some cases of wine, brandy

and soda and home-baked cake are brought out. The new father's

mother and mother-in-law had sent them along for the occasion.

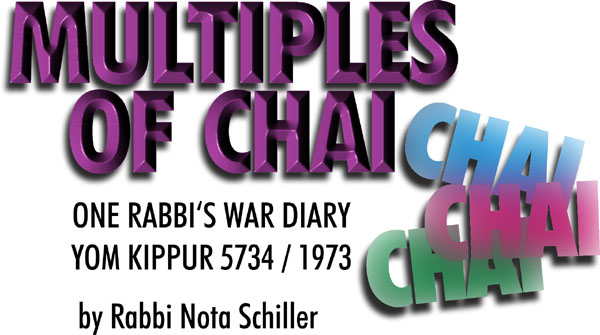

This, of course, is a Jewish army. I learned that the best way

to open a Coca-Cola in the desert is with the back of an Uzi rifle.

As if it were measured to size, a perfect bottle opener. Somebody

turns on a transistor on the side - the fighting at the Suez,

the clashes at the Golan are intense, vicious - blood is being

spilled. Somebody's brother, somebody's father, is being maimed,

killed. Who knows, maybe Hussein will come down this Roman road

tomorrow and we too will get our chance. For now it is quiet and

the huddled group around the transistor, as if by consent, decide

to fill that quiet with a song, a song that is a prayer, a song

that is a declaration.

There is a break, and one of the soldiers runs

up to the mike and says, "There is another reason for our

simcha tonight." and explains that one of the soldiers' wives

had had a boy only that morning. Somebody brought the message

from Jerusalem with our caravan. The father is dragged out into

the center. A handsome, rugged-looking young man. Two friends

lift him on to a third fellow's shoulders and the singing and

dancing erupt again. At the next pause, some cases of wine, brandy

and soda and home-baked cake are brought out. The new father's

mother and mother-in-law had sent them along for the occasion.

This, of course, is a Jewish army. I learned that the best way

to open a Coca-Cola in the desert is with the back of an Uzi rifle.

As if it were measured to size, a perfect bottle opener. Somebody

turns on a transistor on the side - the fighting at the Suez,

the clashes at the Golan are intense, vicious - blood is being

spilled. Somebody's brother, somebody's father, is being maimed,

killed. Who knows, maybe Hussein will come down this Roman road

tomorrow and we too will get our chance. For now it is quiet and

the huddled group around the transistor, as if by consent, decide

to fill that quiet with a song, a song that is a prayer, a song

that is a declaration.

A soldier says to me, "I am not religious,

but I would forget my name before I forget these hakafot."

And deep down in my heart, I know that just as I have never seen

the stars so clearly, so brightly, as I am seeing them now through

the pure ether of this high desert mountain overlooking the wadi,

I know that I have never seen these Jews so brightly, so effervescently

as I see them now. Their eyes burn with an intensity as cold and

as new as the stars. On the road home through the Arab habitations

around the Mount of Olives down through east Jerusalem, the blackout

is still in full force. There is an eerie quality to the thick

darkness that envelops the city.

Back Home... | Encounter On The Golan | Now, The Waiting Starts Again...

Back Home...

The usual post-Sukkot vacation has been called

off at our yeshiva. The American and Canadian boys have all remained

despite pleas from many of their parents to return home. Learning

is a dimension of prayer for us, a ritual of devotion. This is

no time for vacation. Some of the boys are doing part-time volunteer

work at the post office or at the pharmaceutical factories. We

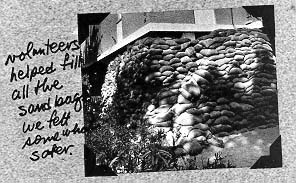

hang up blankets on the windows to keep the blackout regulations,

and I begin a lecture in the tractate of the Talmud that we have

decided to learn this semester. The Rabbi, the instructor, in

the class across the hall arrives in his uniform. The tzitzit

hang out at his sides - somehow, all part of the uniform.

The usual post-Sukkot vacation has been called

off at our yeshiva. The American and Canadian boys have all remained

despite pleas from many of their parents to return home. Learning

is a dimension of prayer for us, a ritual of devotion. This is

no time for vacation. Some of the boys are doing part-time volunteer

work at the post office or at the pharmaceutical factories. We

hang up blankets on the windows to keep the blackout regulations,

and I begin a lecture in the tractate of the Talmud that we have

decided to learn this semester. The Rabbi, the instructor, in

the class across the hall arrives in his uniform. The tzitzit

hang out at his sides - somehow, all part of the uniform.

A few new students have come to the yeshiva. They come as volunteers and find there is no need for them. One is an ex-marine from Virginia, another, a paramedic, and a third, a graduate student who "just felt he had to be here now." None can read Aleph-Bet, but something in them wants to know now what is this thing called Judaism. They register for our three-month beginners program.

People in the streets talk about the Russians coming; we read that portion of the Haftarah that talks of the war of Gog and Magog in the end of days preceding the coming of the Messiah. The storekeeper, the policeman, the cab driver, the nurse, say maybe this is it. The count-down between America and Russia.

A few great rabbis are quoted as having made predictions and then we hear denials of the quotes.

There is criticism, unhappiness, about the

lack of having been prepared. There is mistrust of the cease-fire.

Why didn't we stall a few days till we could deal a severer blow

to Egypt. Obviously the Russians only wanted a cease-fire because

this blow seemed imminent. And what does it mean? How soon will

the next war be? The solders are still away. The Arabs will not

give POW lists. Europe has buckled to Arab oil pressure. America

has helped. But...

Back Home... | Encounter On The Golan | Now, The Waiting Starts Again...

Encounter On The Golan

Then past the evacuated refugee camps, beyond

Jericho, speeding through the arid desert of the Jordan Valley,

through the naked desolation. Two hours drive on towards Beit

Shean, where the Jordan slithers into the Kinneret and the low-lying

lands suddenly erupt with greenness and vegetation. The Kinneret

like a shimmering, silver pearl set in its ring of lavender mountains.

Then past the evacuated refugee camps, beyond

Jericho, speeding through the arid desert of the Jordan Valley,

through the naked desolation. Two hours drive on towards Beit

Shean, where the Jordan slithers into the Kinneret and the low-lying

lands suddenly erupt with greenness and vegetation. The Kinneret

like a shimmering, silver pearl set in its ring of lavender mountains.

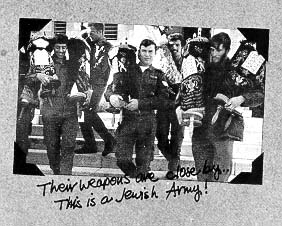

Climbing the twisting mountain roads to Rosh Pina. There receiving our Army Rabbinate guides and passes to visit the outposts on the Golan. We need a special pass to go beyond the "purple line" that designates the new bulge into Syria, because there is till a "dripping" of artillery fire falling there. From the moment that we cross over the Bnot Yaakov Bridge an ironic calm grabs us. The first tanks we see are remnants of the Six Day War, when our soldiers had to walk up a wall imbedded with Syrian bunkers to get the Golan. The Syrian Customs House, now a check point for soldiers leaving the Heights, military police inspecting for booty. The armored division camps "Storm" and "Hurricane", their tanks resting as if exhausted from the raging clashes. Soldiers wave us down, they want prayer books, Tehilim (Psalms) and tefilin.

Out in the fields the twisted, broken steel of burnt-out war machines. Syrian tanks ironically immobile, tranquil. The mountain air is exhilarating, the day brilliantly clear: it seems the wrong place, an impossible scene for so much death. We meet the Hevra Kadisha - mostly religious soldiers who had retrieved bodies and limbs from smoldering tanks for burial. It was nasty work and the secular kibbutznik with the sun-browned face says the "Hevra" are great men.

Through the ghost town of Kuneitra: this once-was city. the shambles, the parts of walls that still stand, pierced with gaping holes. A vanished civilization. The extroverted camaraderie catches you, the vestiges of formality have been left down below; here up on the Golan, the immediacy, the quickness, the closeness of communication. The snow-capped Hermon majestically dominating the horizon: we're back up there now. Perhaps more purple that hue, it has been stained with young blood.

Khan Irnava, a primitive Arab village, mud and straw huts, discs of drying cow dung piled for building, the maze of interconnecting courtyards, no plumbing. In the improvised synagogue, a side wall ripped apart from the shelling, the roof of bamboo reeds open in spots, a small ark has been set on overturned empty ammunition boxes. We pray, I speak, and as I speak the 40 or so soldiers huddle together in the hardly lit, unheated cold of the Syrian night, their faces cast a strange spell over me. By all accounts and measurements these men have acquitted themselves superbly. They are unquestionably superior soldiers. But these boys and men do not have the eyes of warriors. These sons of King David know that if there is a time to fight they must fight, but David wrote the Psalms as well and that was the distilled essence of his soul, of a Jew's soul. They do not hate the Arabs. But they are outraged at stories of torture and murder of POW's.

After the lectures we talk deep into the night. They want to talk about death. About whether there is an afterlife. About how can the world be so callous and immoral to spill out blood to make room for oil. Walking through the mud and rubble, sipping coffee in tents, through the entire night jeeps and halftracks in constant movement in and out of the village. Why didn't the Syrians keep going? One thousand, five hundred tanks with no opposition left. Why did they stop? Can that be called a miracle. Nonsense, says the officer, we found their plans and they had no intention of going any further. Double-nonsense, say I, those plans were made before they knew how easy it was going to be for them to come through!

And what about their attacking on Yom Kippur, another soldier interjecting, that was calculated to catch us off guard. Yet, given our state of unpreparedness, the quick mobilization was only possible because it was Yom Kippur - that is the only day of the year that 85 percent of the country is either at synagogue or home and the roads are empty.

We argue about the validity of secular Zionism, how values such as self-sacrifice and patriotism, if they are to be absolute and binding, must have their source in the Absolute. But even the arguments are within the family, and we can jostle each other affectionately to press our points, and paragraphs are punctuated with swigs from the bottle of brandy that is passed around to relieve the sting of the night air chill. Stories of tanks blown out from underneath them, of wandering behind enemy lines for days.

Kinship with Jews all over the world is openly

acknowledged and appreciated. They are fascinated at Jewish commitment.

A few are cynical about money-giving as an easy way out - but

most are sincere and proud that they can count on that commitment.

The desertion by our allies and so-called neutral nations that

shocked him into a new sense of his own Jewishness, says the division

doctor. "Till now I was an Israeli, now I have become a Jew."

It is a line in the Torah I offer: "There is a people that

dwells apart, not reckoned among the nations" (Numbers 23.9).

Which has been understood to mean that if they forget this solitary

destiny, then the reminder will come through nations not reckoning

with the Jews.

Back Home... | Encounter On The Golan | Now, The Waiting Starts Again...

Now, The Waiting Starts Again...

Though the rumors of the number of casualties

run much higher, the published reports are 1854 dead, and 1800

wounded. It hits me that the war lasted 18 days and we are abounding

in multiples of chai. Without any pretense to being hot on the

trail of a visionary revelation, it yet occurs to me to look at

the 18th weekly portion in the Torah, the 18th

line. I check it and it reads: "When men quarrel and one

strikes the other with a stone or a fist, and he does not die

but has to take to his bed..." (Exodus 21:18). Looking

further, I discover the Midrash (Shmot Raba 30) says that

this is referring to Egypt attacking Israel: "gangsters entering

the vineyard of the king." That Pharaoh will not be consoled

for his losses at the Red Sea until he sees the massive destruction

of Gog and Magog. And one of the commentaries points out that

this idea of Egypt attacking in the vineyard of the Lord - meaning

Israel - has its origin in the line "...little foxes that

ruin the vineyards" (Song of Songs 2:15), which is

interpreted by the Midrash (S.R. 22) to be a reference

to Egypt attacking Israel, an Egypt like "little foxes"

because she is clever - always looking behind her to see who is

there, to check on who is backing her!

Though the rumors of the number of casualties

run much higher, the published reports are 1854 dead, and 1800

wounded. It hits me that the war lasted 18 days and we are abounding

in multiples of chai. Without any pretense to being hot on the

trail of a visionary revelation, it yet occurs to me to look at

the 18th weekly portion in the Torah, the 18th

line. I check it and it reads: "When men quarrel and one

strikes the other with a stone or a fist, and he does not die

but has to take to his bed..." (Exodus 21:18). Looking

further, I discover the Midrash (Shmot Raba 30) says that

this is referring to Egypt attacking Israel: "gangsters entering

the vineyard of the king." That Pharaoh will not be consoled

for his losses at the Red Sea until he sees the massive destruction

of Gog and Magog. And one of the commentaries points out that

this idea of Egypt attacking in the vineyard of the Lord - meaning

Israel - has its origin in the line "...little foxes that

ruin the vineyards" (Song of Songs 2:15), which is

interpreted by the Midrash (S.R. 22) to be a reference

to Egypt attacking Israel, an Egypt like "little foxes"

because she is clever - always looking behind her to see who is

there, to check on who is backing her!

Hospital wards are full of wounded soldiers, many amputees. A one-armed, black-eyed young soldier grins and asks for tefillin. "When I had two arms I didn't wear them. Now I have one arm left, I think it's time. What do you think?" I find it hard to smile and choke back the cry in my throat. Turning away so he shouldn't see my tears, I wind the tefillin around his arm.

Even now it is still in process. Mr. Kissinger is an artist, but artists tend not to be didactic. The beauty of their creation is self-justifying. We are but a part of this massive mural he is designing that will immortalize him. Is it really possible for a little dependent democracy to exist side by side with sprawling dictatorships? Can they afford paying the price of giving up a convenient scapegoat for all their internal problems? The morning papers have a photo of Kissinger smiling with Sadat, but the grocery man's son was killed yesterday, despite the cease-fire, despite the smiles.

Men have died so that we may live. Their purpose in dying was that we might live. What is our purpose in living? And can a nation be purely secular and still call upon its people to make superhuman sacrifices? Can idealism as whim suffice to sustain the galloping needs of our times? Today, tomorrow, the denouement is in process. Such are some of the questions, the options, the multiples of chai.