The Four Sons

The Torah refers to four sons: One wise, one wicked, one simple and one who does not know how to ask a question. What does the wise son say? "What are the testimonials, statutes and laws Hashem our G-d commanded you?" You should tell him about the laws of Pesach, that one may eat no dessert after eating the Pesach offering.

What does the wicked son say? "What does this drudgery mean to you?" To you and not to him. Since he excludes himself from the community, he has denied a basic principle of Judaism. You should blunt his teeth by saying to him: "It is for the sake of this that Hashem did for me when I left Egypt. For me and not for him. If he was there he would not have been redeemed."

What does the simple son say? "What's this?" You should say to him "With a strong hand Hashem took me out of Egypt, from the house of servitude."

And the one who does not know how to ask, you start for him, as the Torah says: "And you should tell your son on that day, saying 'It is for the sake of this that Hashem did for me when I left Egypt.'"

The passage of the four sons raises many questions:

The wise and wicked sons seem to be opposites, but then why isn't the wise son called 'the good son?'

Is the simple son the opposite of the one who does not know how to ask? If so, how are they opposites?

The simple son's question - "What's this?" - is as simple as can be. Who, then, is the son who does not even know how to ask? A little baby?

The wicked son is told: "It is because of this that Hashem did 'for me' when I went out of Egypt - for me and not for him - had he been there he would not have been redeemed." Why is the wicked son answered in third person?

The verse used to answer the wicked son is the same verse used to answer the one who does not know how to ask. Why?

The sons divide into two pairs - the wise and the simple on one side, and the wicked and the one who does not know how to ask on the other.

The simple son wants to learn. He looks up to the wise son and emulates him. When he hears the wise son asking questions, he also wants to ask. His question 'What's this?' lacks the sophistication of the wise son's question, but it reflects the same sincere desire to learn and understand.

The one who does not know how to ask admires the wicked son. He desires to show the same ironic contempt for the Torah, but unlike the wicked son he lacks the requisite cleverness. Not trusting himself to attack as effectively as his mentor, he remains silent.

The wicked son's 'question' is merely rhetorical - it deserves no response at all. Yet,

the one who does not know how to ask is sitting at the table listening to the wicked son's

remarks. He's in danger of being influenced. Therefore, our response to the wicked son is

to say to the one who doesn't even know how to ask: "Don't be influenced by his smug

cynicism. Had he been in Egypt, he would not have been redeemed. He is cutting

himself off from the eternity of the Jewish people."

This difference in approach is described in the book of Proverbs (26:4,5): "Do not answer the fool according to his foolishness, lest you become equal to him. Answer the fool according to his foolishness, lest he be wise in his own eyes." This seems like a contradiction: Should we answer the fool or not?

The answer is that there are two types of fools. One type of fool already 'knows' everything. For him, discussion is merely an opportunity to show off his 'superior' knowledge. There is no point in answering him, because he will never admit a fault. On the contrary, our attempts to educate him will meet with ridicule. As he rejects our insights one after another, the fruitlessness of our efforts makes us appear foolish.

But there is another type of fool: One aware of his limitations. His views are wrong and foolish, but he's not completely closed to instruction. If we open the lines of communication we can have an impact on him. If we don't reach out to him, he'll eventually start to think: "I've held these views for so long, and no one has ever contradicted me - so, I must be right!"

There is a profound message here for our times. We are all confronted with people who scoff at the Torah. We often have to decide if and how to respond. The book of Proverbs teaches us that our primary responsibility is to improve the critic by our response. If that is impossible, then responding is a waste of time. But if it is possible, then we must not wait for his initiation. We must reach out to him and start the dialogue.

Notice, however, that the wicked son is at the Seder! We do not exclude him or reject him personally. Only discussion is avoided, since discussion has no point. The inclusion of the wicked son at the Seder expresses our conviction that no Jew is ever irretrievably lost. We hope our stern response will shake his proud self-confidence to the point where real discussion becomes possible.

"Who is wise? He who learns from every person (Pirkei Avos 4:1)." Indeed, the classical title for a Torah scholar is 'Talmid Chacham' - a wise student.

What is the idea behind this definition? In order to learn from others, one needs two crucial insights. First, "I am lacking. There is much that I do not know." And second, "Others possess the knowledge which I need."

Now we can appreciate why the Haggadah juxtaposes the wise and the wicked sons. The

central failure in the wicked son is his close-mindedness. The heart of his evil is the

supreme foolishness to think that his understanding is perfect. Thus he is the diametrical

opposite of the wise son who is completely open to the instruction of others.

Written by Rabbi Dr. Dovid Gottlieb

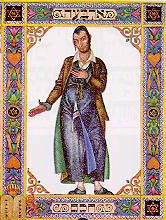

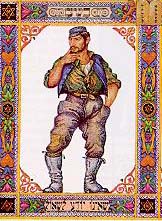

The picture of the 4 sons on the top of page is from the Haggadah of Moses Loeb ben Wolf (Trebisch Moravia, 1716/17)

The colorful 4 sons pictures on the side of the page are from Arthur Syzk Haggadah (Poland and USA, 1939).